Studying Abroad

I honestly can’t quite believe I’m writing my final blog post – this has been such a large part of my year abroad but, 15 posts later, here we are at the 16th and final one!

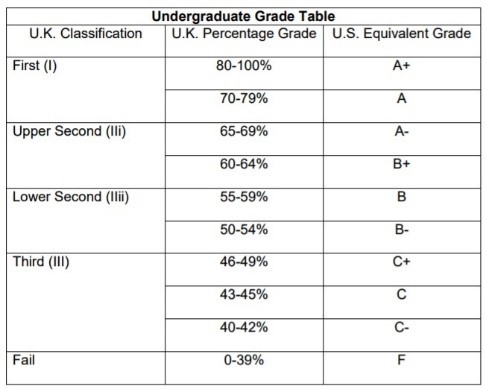

2017-2018 has honestly been one of my best years yet – I’ve lived abroad before (I was actually born in South Carolina and have since lived in Paris and the Netherlands), but being able to study at a foreign university gives you a truly unique experience. I’ve made clear in quite a few blog posts that I prefer geography teaching back at UCL, in terms of the examination styles in addition to the whole degree structure. Whilst you have a broad range of modules to choose from at UCLA, this tends to mean that all geography lectures are at a lower level, as lecturers can’t assume that all students have learnt certain topics and theories.

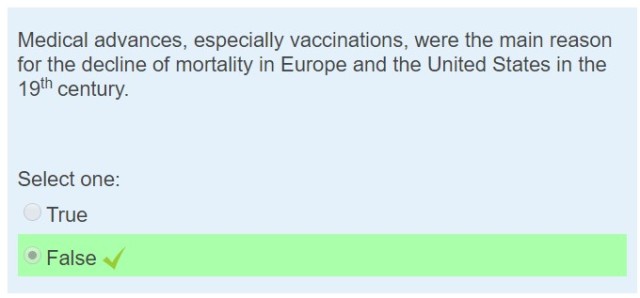

It’s also been interesting to study at a university with upper and lower division courses – whilst courses at UCL are carried out by year (Geog1001, 2001 and so on), courses at UCLA from 1-99 are lower division whilst 100+ are upper division (with upper division being harder). I’ve chosen to do a lot of upper division courses to ensure that this year actually means something for my learning – I think this has reflected well in my blog where I’ve had new topics to talk about, rather than choosing the easy options. Specifically, my favourite course so far has been UP232 (Disaster Risk and Reduction) – I’m so happy to have been selected for a graduate course and, in all seriousness, it’s a topic that I’m now considering as a post-graduate study option. From initially studying Geog2014 at UCL, being able to continue my learning of development geography from a different perspective at UCLA has opened new doors and showed me what I’m most interested in.

Blogging Abroad

One of the most interesting tasks I’ve had to do so far at UCL was write a reflective essay on my original essay in Geog2024 – it’s been one of the only opportunities at UCL where I’ve had to step back and truly look at the work I’ve completed. In this style, I’d like to briefly reflect on some of the main takeaways and reasonings behind the evolution of Colouring in Abroad.

Initially, I found it slightly difficult to create a direction for the blog – as my wide variety of module choices out here has shown, I’m interested in studying a lot of different topics and drawing these all together in a single web page has been challenging. However, I’d say that the need for direction also challenged me to be more analytical in what I’m learning about on a weekly basis. Rather than just taking notes in class, blogging forces you to focus analytically upon what you’re presently learning and putting this into perspective with what you’ve learnt in the past – I’m constantly linking what I’m learning here at UCLA to UCL on a broad range of topics – from Malthusianism, terrorism, developmental perspectives of Brazil and so on.

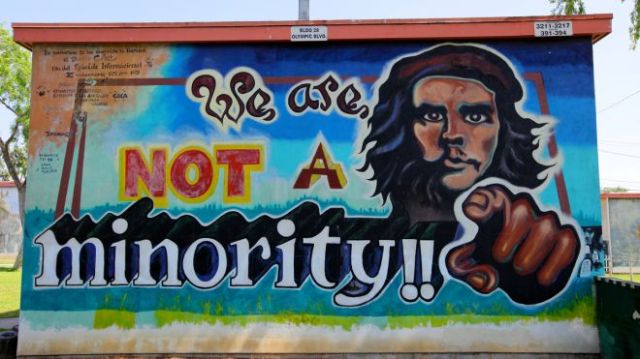

I’m coming out of this year with a new-found respect for blogging – it’s not something I’ve ever had to do before (or even thought about doing) and it takes a huge amount of work – excluding this final post, my blog totals over 15,000 words and I’ve written more posts than necessary for the module (can I just use this entire website for my dissertation?!). I decided to structure my blog in a chronological order, using topics from modules that I was studying in Fall, Winter and Spring quarters – as time has passed, I have also been able to supplement blog posts with any information that is relevant from previous quarters. I think my blog has gained greater clarity and direction as time has gone by, and I hope this comes through to those reading as well. Making a blog has also been a new experience engaging with an online audience – embedding gifs, videos, hyperlinks and maps into my posts have all been very conscious efforts to make posts come to life in various ways (one of my pictures from the blog even made its way onto the UCL Study Abroad Instagram page – see below!).

Some posts are more independent than others – specifically regarding my social media and gerrymandering posts – but as I’ve researched issues that began as being mostly independent from my lecture content, I’ve found that these larger issues commonly relate back to content from both UCL and UCLA. I think that with blogging, there’s always more that could be said and each blog post that I’ve written tends to raise several more issues that I could write about! There’s therefore much more to potentially expand upon if I were to continue this blog in the future and I’m sad that the blog deadline finishes before my actual studies finish – I may write a few more posts just for a sense of fulfilment so I’ve got a memento of my entire academic year.

There’s obviously no right and wrong with personal blogging, but I’m intrigued as to how my year may have differed if my studies here had counted towards my overall degree. I’m really grateful that this year doesn’t count, as it’s meant I’ve chosen subjects purely because I enjoy them. This has given me more time, and more enthusiasm, in writing my academic blog posts. Although I’m excited to begin final year and continue with my dissertation, I’m heartbroken that this year has come to an end so quickly. Thank you to everyone who has made my time here so special – I don’t want to sound too much of a cliché but, socially and academically, it’s been one of the best years of my life.